To my French-Canadian friends, I will always be the “guy from France”. My French accent, my history and cultural references are pretty much foreign to them. Despite this, they have embraced me and I have been an active member of the Franco-Ontarian educational world for the last 30 years. But, I don’t really belong to either solitude.

Most of my work colleagues have no idea I speak fluent English without any discernable accent. In fact, most have never heard me speak anything but French. Such are the privileges of working in a French speaking workplace.

Once, whilst in Timmins, a French-Canadian teacher’s jaw dropped when I answered my cell phone in Canadian English. I was evidently perceived as European French, how could it be that my English wasn’t riddled with French diphthongs?

When you’re an active member of the French-Canadian community, you’re expected to fully subscribe to several causes, one most notably, is the issue of language, our “cause célèbre”. And yes, sometimes I feel guilty when I press “English” at the ATM, or read an English instruction manual. So, I compensate by changing the language of my electronic devices to French, requesting French language services in court, or pressing 2 when I call customer service: it’s also quicker.

My Franco-Ontarians friends and colleagues have taught me something I could never have learnt in France: never take a language for granted.

There are times and places where you must fight to keep it alive. Like the old Basque adage says: “When a language disappears, it’s not because people no longer learn it, but when those who do speak it, no longer use it.”

Quite a few of my French compatriots assume that I immigrated to Canada, just like they did. I sound like them, talk like them, walk like them, so it makes perfect sense that I should also be a first-generation immigrant, a new Canadian. True, I was not born here, but I’ve always been a Canadian citizen as well as a card-carrying Frenchman.

To my English-speaking friends and acquaintances, I’m the “French guy with no discernible accent”. I often feel like the character Lieutenant Archibald “Archie” Hicox from Inglourious Basterds, just a slight mistake away from giving up my other nationality.

Still, when new acquaintances learn that I speak what they gleefully call “Parisian French”, they open the flood gates of good old French-Canadian-Bashing: “oh you speak ‘real’ French, not like what they speak in Quebec”. To which I invariably respond by saying it’s true, French Canadian is as different from French spoken in France as Canadian English is to Received Pronunciation, i.e. the Queen’s English.

I’ve put enough effort over the years to counter French-Bashing, especially under the George W. Bush presidency, to not want to go along with bashing my French-Canadians friends and colleagues. Their French is different? So is the English spoken in Newfoundland, Texas or Tangier, Virginia.

How is it that my spoken English is free of French overtones? English was my mother tongue and my mother’s tongue. She was a tiny yet fierce woman, born in Cape Breton, schooled in Hamilton and Toronto, a University of Toronto graduate.

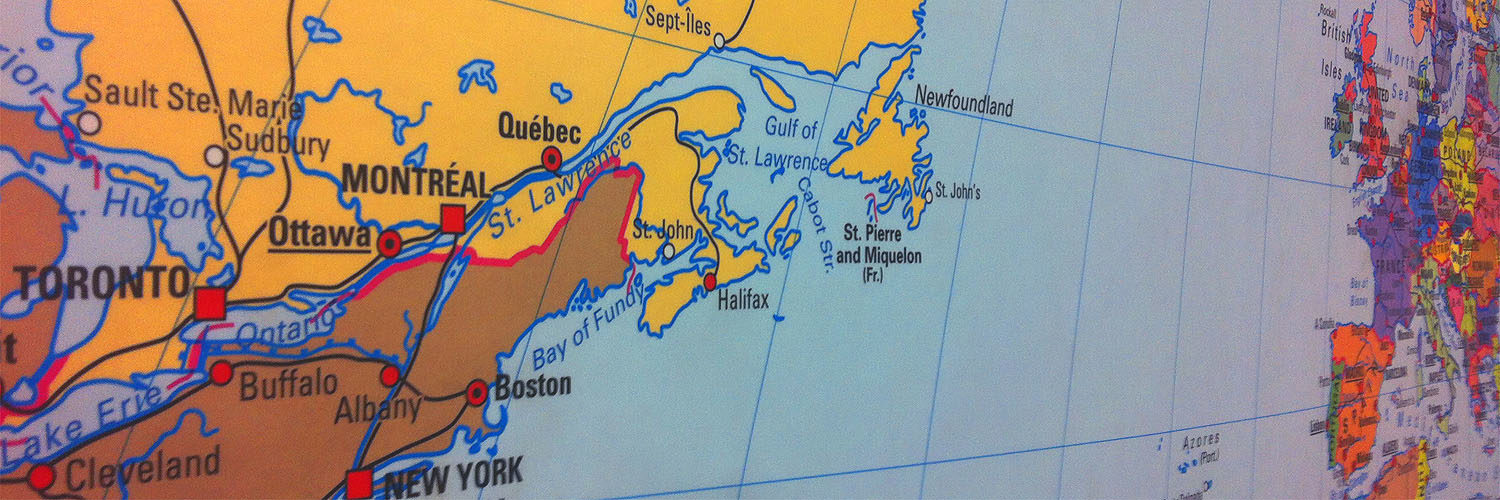

My mother, a lifelong learner, wanted to perfect her university level French. So she participated in a French Immersion program in a French colony in the middle of the ocean, 12 miles from Newfoundland.

On the first night there she thought she met the mayor of the tiny village who was a snappy dresser and floated around the dance floor like Fred Astaire. He asked her to dance.

The next day, the same man showed up at her boarding house on his way to work. He was wearing a flannel, plaid shirt jacket with cigarette dangling from his lips. Overnight the Mayor turned in a Ship mechanic.

My Mother eventually settled and married my ubiquitous father, a music and food loving French citizen. Thus, I became the Franco-Canadian version of The Orange and the Green – my mother was a Liberal Federalist and my French father would cheer for Quebec.

Being of Acadian extraction, memories of what happened in 1755 doesn’t fade over generations. My Father was French, but his family had been in North America since 1644: they had sought refuge in the last French island in North America following the collapse of the French Colonies of Quebec and Acadia. His ancestors faced two more deportations, in 1778 and 1793 for the high crimes of being French and Catholics and being too close to British North America and its overzealous Brigadier Generals.

My father was as French as French could be. He loved his saucisson, listened to Georges Brassens, voted for De Gaulle, Pompidou and Giscard and was almost drafted into the Algerian War, only to be let go because of a few extra pounds.

Growing up in Saint-Pierre et Miquelon, if you didn’t guess that already, my television world was limited to two channels. CBC from Marystown Newfoundland and France Régions 3, a state controlled French channel with such 70s classics as les Chiffres et des Lettres and Apostrophes. My childhood was a mixture of the Friendly Giant, Mister Dressup and Casimir and Hippolyte.

I’d watch Westerns every Sunday, as did most of France, convinced John Wayne spoke some sort of Mid-Atlantic French (there is no such thing in case you’re wondering). Imagine my surprise, and disappointment, when I heard “The Duke” for the first time.

Radio on the other hand, endlessly teased my curiosity via medium wave and shortwave broadcasts traveling large distances. I would listen to the BBC, WCBS New York and even Radio Moscow International.

A quarter century later, in Toronto, I mostly listen to podcasts from France, not Radio-Canada nor CBC. I’m not trying to be a contrarian, it’s just my way of actively keeping up with French culture, French language: both are dear to me.

And that’s because I’m French. I’m Canadian. But, I’m not French-Canadian

Leave a Reply